Making of the first molecule of the month story - Myoglobin

Making of the Story

This story is built as a careful translation—from scientific insight to narrative experience.

We start with the original Molecule of the Month content by David Goodsell:

https://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/1

We use ChatGPT to transform the written explanations into clear, descriptive audio narration while preserving the scientific intent and rhythm of the original text. The narration is then brought to life using Evernote’s AI text-to-voice tool, generating a natural female voice-over that guides the viewer through the story:

https://evernote.com/ai-text-to-voice. Note that the audio will not play here; this example simply shows how to specify it.

Rather than reinventing the narration, we closely follow David’s structure, breaking it into distinct scenes that unfold step by step. Each scene focuses on a specific idea, visual moment, or molecular insight, allowing the story to remain accessible and faithful to the source material.

To support this process, we prepare each story using a shared set of helper functions and utilities—defined once and made available across all scenes through story-wide code. This allows us to focus on storytelling and visualization while keeping the technical foundation consistent and reusable. This code is available to all scenes in the story. Throughout the scenes, we will use primitives, selectors, and animations, as well as audio playback through customization of the builder. We will also use advanced features from the molstar customisation of the markdown syntaxe.

Story Options

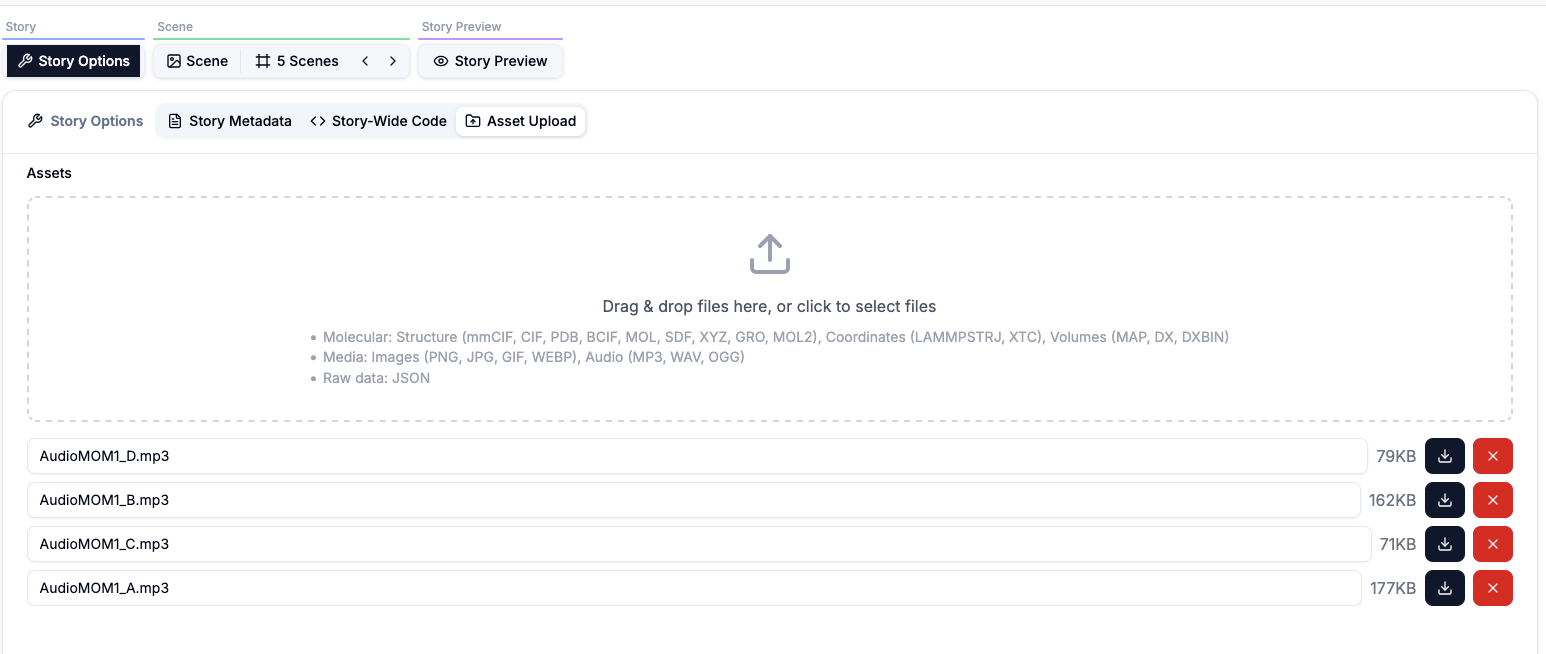

In the story options we can specify metadata such as title, authors note. This is also where we provide story-wide reusable code and also where the asset are upload. In this story the only asset is the audio description for each scene.Story-Wide Code

// All Mol* library functions are available in scope:

// - Vec3, Mat4, Mat3, Quat (from mol-math)

// - MolScriptBuilder as MS (from mol-script)

// - decodeColor, formatMolScript (from mvs)

// - builder (the MVS builder instance for each scene)

// Transformation matrices as plain arrays

// These will be converted to Mat4 by the transform function

// 1pmb->1mbn alignment

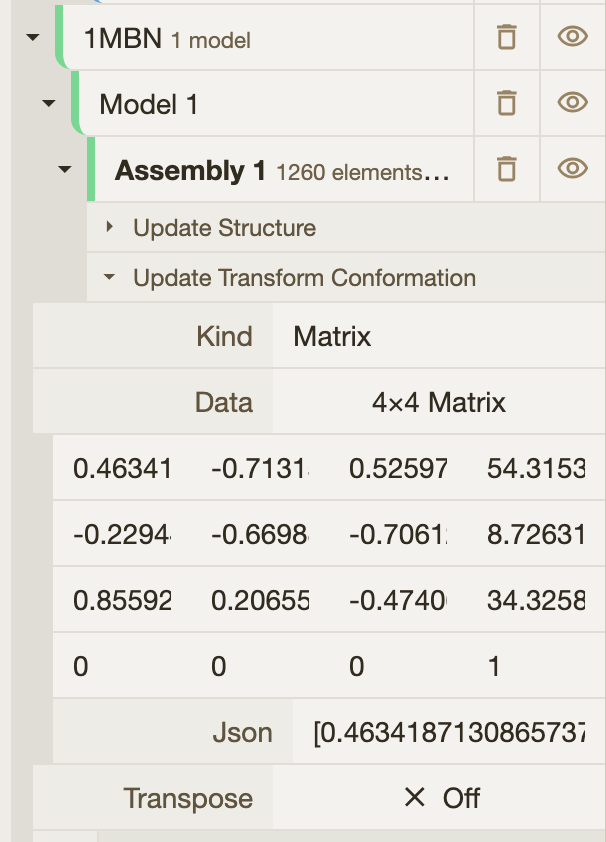

const alignMatrix = [

0.4634187130865737, -0.7131589697034304, 0.5259728687171936, 0, -0.22944227902330105, -0.6698811108214233,

-0.7061273127008398, 0, 0.8559202154942049, 0.2065522332899299, -0.4740643150728161, 0, -52.54880970106205,

37.49099778180445, -6.133850309914719, 1,

];

// 1mbo->1myf alignment

const alignMboMatrix = [

-0.8334619943964441, -0.512838061396133, -0.20576353166796402, 0, -0.20145089001561267, 0.628743285359846,

-0.7510655776229758, 0, 0.5145474196737698, -0.5845332204089626, -0.6273453801378679, 0, 11.864847328611186,

-1.5261713438028912, 23.638919347623467, 1,

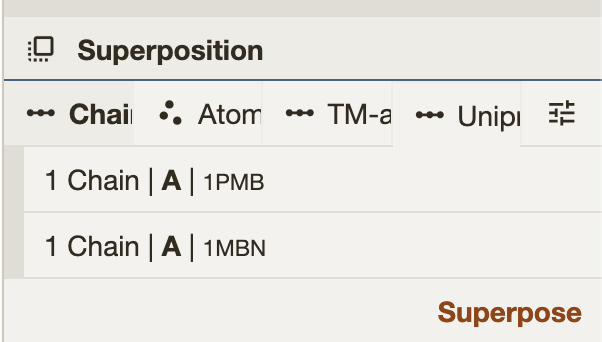

];Mol*’s Superposition tools provide a 4×4 transformation matrix for the alignment. After running the superposition, the matrix can be retrieved from the hierarchy tree. Simply click on the json input field to copy the matrix.

|

|

// Color theme helper function - using const to ensure proper scoping

const ill_color = (color, carbonLightness) => ({

molstar_color_theme_name: 'illustrative',

molstar_color_theme_params: {

style: {

name: 'uniform',

params: {

value: color, // Pass color string directly

saturation: 0,

lightness: 0,

},

},

carbonLightness: carbonLightness, // required parameter

},

});

//Decimal color code for Grey (128, 128, 128)

// you can use tools like [https://convertingcolors.com/](https://convertingcolors.com/) to convert between different color format, RGB,HEX,Decimal etc…

const GColors2 = ill_color(8421504, 0.8);

/* Color scheme from David Goodsell illustrate software */

// David colors can be retrieve from the [illustrate web server](https://ccsb.scripps.edu/illustrate/) , of using Eyedropper tool.

const GColors3 = {

schema: 'all_atomic',

category_name: 'atom_site',

field_name: 'type_symbol',

palette: {

kind: 'categorical',

colors: {

C: '#FFFFFF',

N: '#CCE6FF',

O: '#FFCCCC',

S: '#FFE680',

},

},

};

// Audio file paths - using local assets directory

// for each scene we have prepared an audio file, preloaded in the asset upload

const _Audio1 = 'AudioMOM1_A.mp3';

const _Audio2 = 'AudioMOM1_B.mp3';

const _Audio3 = 'AudioMOM1_C.mp3';

const _Audio4 = 'AudioMOM1_D.mp3';

// Helper function to get PDB URL - using const for proper scoping

const pdbUrl = (id) => {

return `https://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry-files/download/${id.toLowerCase()}.bcif`;

};

// Helper function to create structure from PDB ID - using const for proper scoping

const structure = (builder, id) => {

return builder

.download({ url: pdbUrl(id) })

.parse({ format: 'bcif' })

.modelStructure();

};

// Helper function to add a "Next" button - using const for proper scoping

const addNextButton = (builder, snapshotKey, position) => {

builder

.primitives({

ref: 'next',

tooltip: 'Click for next part',

label_opacity: 0,

label_background_color: 'grey',

snapshot_key: snapshotKey,

})

.label({

ref: 'next_label',

position: position,

text: 'Next Scene →',

label_color: 'white',

label_size: 5,

});

};

// Helper function to create an ellipsoid (for salt bridges) - using const for proper scoping

// Accepts plain arrays or Vec3 objects as positions

const getEllipse = (builder, pos1, pos2, ref) => {

// Convert arrays to Vec3 if needed

const p1 = Array.isArray(pos1) ? Vec3.fromArray(Vec3(), pos1, 0) : pos1;

const p2 = Array.isArray(pos2) ? Vec3.fromArray(Vec3(), pos2, 0) : pos2;

const center = Vec3.add(Vec3(), p1, p2);

Vec3.scale(center, center, 0.5);

const major_axis = Vec3.sub(Vec3(), p2, p1);

const z_axis = Vec3.create(0, 0, 1);

// cross to get minor axis

const minor_axis = Vec3.cross(Vec3(), major_axis, z_axis);

return builder.primitives({ ref: ref, opacity: 0.33 }).ellipsoid({

center: center,

major_axis: major_axis,

minor_axis: minor_axis,

radius: [5.0, 3.0, 3.0],

color: '#cccccc',

});

};

// Helper function to build the 1mbn structure with common representations - using const for proper scoping

// We also keep a reference to the object's opacity for later animation.

const build1mbn = (builder) => {

const struct = structure(builder, '1MBN');

struct

.component({ selector: 'ligand' })

.representation({ ref: 'ligand', type: 'ball_and_stick' })

.color({ color: 'orange' });

// FE and O should be spacefill

struct

.component({ selector: { auth_seq_id: 155, label_atom_id: 'FE' } })

.representation({ type: 'spacefill' })

.color({ color: 'yellow' });

struct

.component({ selector: { auth_seq_id: 154 } })

.representation({ type: 'spacefill' })

.color({ color: 'blue' });

const chA = struct.component({ selector: { label_asym_id: 'A' } });

chA

.representation({ type: 'surface', surface_type: 'gaussian' })

.color({ color: '#ff0303' })

.opacity({ ref: 'surfopa', opacity: 0.0 });

chA

.representation({ type: 'line' })

.color({ custom: { molstar_color_theme_name: 'element-symbol' } })

.opacity({ ref: 'lineopa', opacity: 0.0 });

chA.representation({ type: 'cartoon' }).color({ custom: { molstar_color_theme_name: 'secondary-structure' } });

return {

struct,

refs: {

surfaceOpacity: 'surfopa',

lineOpacity: 'lineopa',

},

};

};

// All helper functions and constants are available globally to scene files

// No exports needed - all code is combined togetherScene 1 Introduction

In the Scene Options section, we specify the scene name and the key first-slide, which can be used to reference this scene and trigger it from another scene using a clickable label.

Markdown description

# Introduction

A story based on the orginal [first Molecule of the Month](https://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/1) made by David Goodsell in January 2000.

*This story includes short audio commentaries to guide you through the structures.*

For the best experience, please keep your sound on or use headphones.MolviewSpec 3D view and code

Scene 2 Molecule of the Month: Myoglobin

This scene adapts the first part of the Molecule of the Month entry on myoglobin into an interactive, narrated visual experience. In the Scene Options, we define the scene key reference (intro) and provide the associated description. The Markdown supplies the scientific narrative—why myoglobin mattered historically, how it stores oxygen through the heme group, and how early pioneers visualized protein structures. The MolViewSpec script then builds a guided animation: it loads the structure, configures visual styles, and progressively reveals the protein and its heme group in sync with the narration. The result is a “read + explore” scene where text, highlights, and motion work together to teach the molecule.

Scene description

# Molecule of the Month: Myoglobin

Myoglobin was the first protein to have its atomic structure determined, revealing how it stores oxygen in muscle cells.

---

## The First Protein Structure

Any discussion of protein structure must necessarily begin with **myoglobin**, because it is where the science of protein structure began. After years of arduous work, *John Kendrew* and his coworkers determined the atomic structure of myoglobin, laying the foundation for an era of biological understanding.

You can take a close look at this protein structure yourself, in **PDB entry [1mbn](https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1MBN)**. You will be amazed—just like the world was in 1960—at the beautiful intricacy of this protein.

---

## Myoglobin and Muscles

[Myoglobin](!query%3Dchain%20A%26lang%3Dpymol%26action%3Dhighlight%2Cfocus) is a **small, bright red protein**. It is very common in muscle cells and gives meat much of its red color. Its job is to **store oxygen**, for use when muscles are hard at work.

To do this, it uses a special chemical tool to capture slippery oxygen molecules: a **[heme group](!query%3Dresn%20HEM%26lang%3Dpymol%26action%3Dhighlight%2Cfocus)**. Heme is a disk-shaped molecule with a hole in the center that is perfect for holding an iron ion. The iron then forms a strong interaction with the **[oxygen molecule](!query%3Dresn%20OH%26lang%3Dpymol%26action%3Dhighlight%2Cfocus)**. As you can see in the structure, the heme group is held tightly in a deep pocket on one side of the protein.

---

## Visualizing Protein Structure

When the structure of myoglobin was solved, it posed a great challenge. The structure is so complex that **new methods** needed to be developed to display and understand it.

- *John Kendrew* used a huge wire model to build the structure based on the experimental electron density.

- Then, the artist *Irving Geis* was employed to create a picture of myoglobin for a prominent article in *Scientific American*.

- Computer graphics were still many years in the future, so he created this illustration entirely by hand—one atom at a time.

You can learn more about the work of Irving Geis at the **[Geis Archive on PDB-101](https://pdb101.rcsb.org/learn/GeisArchive)**.

*Illustration of myoglobin by Irving Geis. You can learn more about this painting at the Geis Archive on PDB-101.

Used with permission from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Copyright 2015.*The scene Markdown here include interactive links that control the 3D viewer. For example:

[Myoglobin](!query%3Dchain%20A%26lang%3Dpymol%26action%3Dhighlight%2Cfocus)This is a special link (not a normal URL). When you hover it, the viewer previews the target, and when you click it, the viewer applies the requested actions: - query=chain A selects the target using a PyMOL-style query - lang=pymol tells the system how to interpret the query string - action=highlight,focus highlights the selection and moves the camera to focus on it

In practice, this lets the narration stay in Markdown while the reader can directly trigger viewer interactions.

Scene MolviewSpec 3D View and Code

Scene 3 Myoglobin and Whales

Scene 3 extends the myoglobin story into an evolutionary and biophysical comparison: why whales can dive so long. The markdown explains the biological motivation—marine mammals carry far more myoglobin and need molecular adaptations to avoid aggregation at high concentration. The MolViewSpec script turns that into a visual side-by-side comparison of sperm whale myoglobin (1MBN) and pig myoglobin (1PMB), then draws attention to key surface mutations by marking charged residues and pulsing a surface representation. The result is a clear “compare and understand” moment where structure, labels, and animation reinforce the narrative.

Scene Description

This markdown is the scene narrative: Establishes the “whale source” fact (Kendrew’s whale myoglobin). Explains the functional reason: high oxygen storage for deep dives. Introduces the hypothesis/mechanism: extra positively charged residues on the surface help reduce aggregation. Sets up the comparison explicitly via PDB links to [1mbn] and [1pmb].

# Myoglobin and Whales

If you look at John Kendrew's PDB file, you'll notice that the myoglobin he used was taken

from sperm whale muscles. Whales and dolphin have a great need for myoglobin, so that they can

store extra oxygen for use in their deep undersea dives. Typically, they have about 30

times more than in animals that live on land. A recent study revealed that a few special

modifications are needed to make this possible.

Comparing whale myoglobin (PDB entry [1mbn](https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1mbn)) with

pig myoglobin (PDB entry [1pmb](https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1pmb)), we find that there are

several mutations that add extra positively-charged amino acids to the surface. Marine animals typically have these extra charges on

the surface of their myoglobin to help repel neighboring molecules and prevent aggregation when myoglobin is at

high concentrations.Scene MolviewSpec Code

Scene 4 Oxygen Bound

Scene 4 (key: oxygen) focuses on the moment oxygen binds to myoglobin—and, more importantly, on the dynamic nature of proteins that makes binding possible. The markdown explains that a crystal structure such as 1MBO is only a single snapshot, while real proteins continuously “breathe” through small conformational fluctuations, creating transient pathways for oxygen to enter and leave. The MolViewSpec script reinforces this idea visually: it shows bound oxygen, animates an NMR ensemble (1MYF) to convey motion, and illustrates oxygen traveling along a path into the binding pocket. The result is a clear, intuitive explanation of how molecular dynamics enables function.

Scene Description

This markdown provides the scientific narrative for the scene: Introduces oxygen binding observed in PDB 1MBO Answers the “how does oxygen get in/out?” question by emphasizing protein dynamics Uses PDB 1MYF as the visual illustration of breathing/flexing motions Frames the viewer’s understanding: the PDB is a snapshot; biology is motion

# Oxygen Bound to Myoglobin

A later structure of myoglobin, PDB entry [1mbo](https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1mbo),

shows that oxygen binds to the iron atom deep inside the protein.

So how does it get in and out? The

answer is that the structure in the PDB is only one snapshot of the

protein, caught when it is in a tightly-closed form. In reality,

myoglobin (and all other proteins) is constantly in motion, performing

small flexing and breathing motions (illustrated here by PDB entry [1myf](https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1myf)). So, temporary openings constantly

appear and disappear, allowing oxygen in and out.Scene MolViewSpec 3D View and Code

Scene 5 Conclusion

Scene 5 (key: end) wraps up the story by connecting myoglobin’s structure to broader principles of protein stability and function. The markdown summarizes classic ideas—hydrophobic residues packed inside, charged residues exposed on the surface, and occasional salt bridges that stabilize local structure—then invites the reader to freely explore. The MolViewSpec script turns those principles into a guided visual: it highlights hydrophobic and charged amino acids with distinct colors, overlays salt-bridge cues using distance measurements and ellipse annotations, and paces the reveal with simple animations. The scene ends with a navigation label that loops back to the start, making the story replayable.

Scene 5 Conclusion

This Markdown provides the concluding narrative and references for the story. It summarizes key structural principles revealed by the atomic structure of myoglobin, including the burial of hydrophobic (carbon-rich) residues in the protein core, the exposure of charged residues on the surface, and the formation of stabilizing salt bridges between oppositely charged amino acids. The text then encourages readers to explore these principles directly in the interactive view. The final sections offer directions for further exploration—such as comparing myoglobin sequences across species or examining cyanide-bound myoglobin—and include a set of primary references that document the historical and scientific context of the structures used in this story.

# Molecule of the Month: Myoglobin

The atomic structure of myoglobin revealed many of the basic principles

of protein structure and stability. For instance, the structure showed

that when the protein chain folds into a globular structure,

carbon-rich amino acids are sheltered

inside and charged amino acids positively

and negatively are most often found on the surface,

occasionally forming salt bridges

that pair two opposite charges (shown here with circles).

To explore some of these principles, explore freely in the interactive view.

## Topics for Further Discussion

You can use the sequence comparison tool to align the sequences of different

myoglobins, looking for mutations. For instance, [here is the alignment of whale and pig myoglobin](https://www.rcsb.org/alignment?request-body=eJyljrsOwjAMRf%2FFcxgqxNKN7kXsqKpC4pZIeZTEVamq%2FDtOGRAzm%2BPje3I3eM4YV6g3CBOZ4FMZI9IcfZ%2BQoVfYa0kS6kHahFmACp7wReXQBY1QwyRNXExCEOCQHkEX5qUrjNxBWjN64GSiOCtWI%2F9y2wA9xbU3fA1V21w4ndCiKjWKQKbVfeiZ0R3HUmhfVIKz%2Bvs8HXMWv75r2%2Fzn61gJg7F71y6%2FARZEZL8%3D&response-body=eJzlU11vmzAU%2FS88Q2RsjKFv7iCA7GRJQFRVVUU0uClSQjo%2BtkVV%2FvuuyUdTadMeurcJIXF97j33HN%2FLm1HVzzvj5s3o%2B6o0bgzlUaZoyaynwvUshznPll8UpVVgRUr1hAkrmWEabVd0fQv5X75OZjLMQuNgGlvVFZqq2FTreqvqbrndlQqSXouq%2BVG1CgqvMNW97HTLbmsNp5qiUW2%2F6YD44Q16NP2q6%2BFoCKGm2S8HkfbkdqpFqI1addWuHpq2%2B%2B0R5QA9qfWyVd%2BGA9uE2vI9pORwMD%2FyzSa3n%2BN7NN%2FlLi8eB92NWgOl9vDwF1YdVnWpfho3yDQ2ql53L0f%2BR%2FMTtaCta4q6fd4126I7a7FNdHp%2B%2BwUd0chxCXY9xjA2LTRiNkWMONT2TDSimDi%2Bz1yHQDaAmGCbeTbxXR25rodsG%2FvHiCGGEHE9D2vukUcpdgnBlEGAEfU9RrFPdKbDqOMT2x8yLYpH1MWOQxzP9U3CRi5lBCGKoKlFR77j2Rg5iNkgVw%2Bg326LZq%2BH165257X5Xmx62EFo68I97F%2F1PsK99apeKasqYUpVtzf0QlwyXeeSuZikwUfQ9y5gNrGGRoYefw1jr5fQtSp7tdQb3w73rxH9G2xUeUa1MI3Aq2XDEHUpzOxUoKPV7rtqirXSqQjmgdDjcctO0v%2B4ZJ%2FYsQs5lOYyDaPwbi5zGed3XOQhD3IexdE8SGSykGORxrMwk6EYB4uxiKXIQh5OBE%2FDQAoRR3mWy4zLiCcQiiiOAZZiJvk8jXkmYpHMEnEvw3GShjxJYuiTLuJZFIwjHvB5xCdTwWUoxwsRJJyLexHK6H4eDdP453YjmQYnu9P8LrqyG%2BZHu9HFrhjsgs9ru9OT3ejabvbBbn5ld57LeSo%2B2E1PdqfB5Gx3rO3%2BH5t9%2BAU7Kf5z&encoded=true) used to create the illustration in this column.

PDB entry [2jho](https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2jho) includes myoglobin poisoned by cyanide. Take a look and you'll see that the cyanide blocks the binding site for oxygen.

## References

- 1mbn: J. C. Kendrew, R. E. Dickerson, B. E. Strandberg, R. G. Hart, D. R. Davies, D. C. Phillips & V. C. Shore (1960) Structure of Myoglobin. Nature 185, 422-427.

- J. C. Kendrew (1961) The three-dimensional structure of a protein molecule. Scientific American 205(6), 96-110.

- 1mbo: S. E. Phillips (1980) Structure and refinement of oxymyoglobin at 1.6 A resolution. Journal of Molecular Biology 142, 531-554.

- 1pmb: S. J. Smerdon, T. J. Oldfield, E. J. Dodson, G. G. Dodson, R. E. Hubbard & A. J. Wilkinson (1990) Determination of the crystal structure of recombinant pig myoglobin by molecular replacement and its refinement. Acta Crystallographica B, 46, 370-377.

- 1myf: Osapay K, Theriault Y, Wright PE, Case DA. Solution structure of carbonmonoxy myoglobin determined from nuclear magnetic resonance distance and chemical shift constraints. J Mol Biol. 1994;244(2):183-197. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1994.1718

- S. Mirceta, A. V. Signore, J. M. Burns, A. R. Cossins, K. L. Campbell & M. Berenbrink (2013) Evolution of mammalian diving capacity traced by myoglobin net surface charge. Science 340, 1234192.Molviewspec 3D view and code

Conclusion

Myoglobin was the first protein whose atomic structure was solved, and it remains a landmark example of how structure explains biological function. Across these scenes, we have seen how a static PDB structure captures only a single moment, while real proteins are dynamic objects whose motion enables processes such as oxygen binding and release.

By combining scientific narration with interactive visualization, this story invites readers to move beyond passive observation and actively explore molecular structure. Highlighting residues, comparing species, and animating motion help translate abstract structural principles into intuitive, visual understanding.

This approach—linking trusted scientific content with interactive, scene-based exploration—can be extended to many other molecules, offering a powerful way to communicate molecular biology to both specialists and broader audiences.